Miriam Darlington was born in Lewes, Sussex, and now lives in Totnes with her two dogs, one cat, two children and one husband. She has tracked and studied wildlife for most of her life and is an avid bird-watcher, expert owl-finder, and top otter-spotter. She has a degree in Modern Languages, a PhD in Nature Writing, a certificate in Field Ecology and is a Nature Notebook columnist at The Times. Her first book, Otter Country, was published in 2012. She currently teaches Creative Writing at Plymouth University and spends the rest of her time writing and researching about wildlife and the people in its grasp.

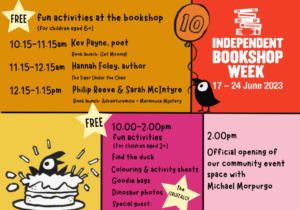

On Thursday 6th December, Miriam Darlington will be at CCB talking about her latest book, Owl Sense. Owl Sense (2018) was a BBC Radio 4 Book of the Week and was longlisted for the Wainwright Prize for Nature and Travel Writing.

Q: What book changed your life?

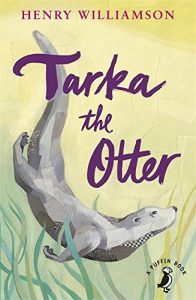

A: Tarka the Otter by Henry Williamson

When I was 10 years old I was given a copy of Henry Williamson’s Tarka the Otter to read. The cover was a scene of shadowy reeds and before them skulked a dark silhouette. With his glistening eyes, whiskered muzzle and stealthy form, Tarka enticed me into his world. An intense sympathy for the feisty but persecuted otter rose in me, especially during the scenes of hunting, and I felt like I was an otter for weeks after reading it. For years after reading Tarka, encouraged by my parents, I searched for the real animal in the river Ouse in Lewes, Sussex where I was brought up. Like many children of my generation, I learned the painful truth that due to pollution otter numbers had dwindled to such an extent that they were extinct here and in most of the counties of England. Later I moved to Devon where, saved by the wild places of the South West amongst the clean, rushing waters high on Dartmoor, the otter had been able to hang on. But it was not until I was an adult and their numbers had recovered that I eventually saw an otter in the wild.

Although in the South West of England we are familiar with what is now called Tarka Country, many people may never have read Williamson’s book. Tarka Country in North Devon has been designated the UK’s first UNESCO Biosphere Reserve due to its uniquely rich ecosystem, partly thanks to the attraction of Williamson’s writing. We have the Tarka Trail, and the Tarka Line, but for me it will always be the description in the story that first connected me to the place:

“Twilight upon meadow and water, the eve-star shining above the hill, and Old Nog the heron crying kra-a-ark! as his slow wings carried him down to the estuary. A whiteness drifting above the sere reeds of the riverside, for the owl had flown from under the middle arch of the stone bridge that once carried the canal across the river.”

I loved the places around the rivers Taw and Torridge that Williamson described, and as an adult became a self-taught naturalist. As my sense of connection to nature became more deeply rooted I wanted to capture that in my writing, to share a story where every one of our senses is summoned and connected to the web of life, just like in Tarka:

“Time flowed with the sunlight of the still green place. The summer drake-flies, whose wings were as the most delicate transparent leaves, hatched from their cases on the water and danced over the shadowed surface. Scarlet and blue and emerald dragonflies caught them with rustle and click of bright whirring wings. It was peaceful in the backwater, ring-rippled with the rises of fish, a waving mirror of trees and the sky, of grey doves among green ash-sprays, of voles nibbling sweet roots on the banks.”

The poet Ted Hughes once remarked that when he read Tarka aged 11, it “entered me and gave shape and words to my world, as no book has ever done since…” I feel the same way.

It is often stories we hear when we are young that alert our sensitivity to nature. These days, however, living in our towns and cossetted by central heating and entertained by digital technology, getting out is not easy for everyone. Sometimes nature comes to us though: one morning, I looked up and perched like an exclamation mark on the balustrade of our balcony was a Tawny Owl. In the weak dawn light its gorgeous camouflage was exposed against the sky: the rust-tinged facial disc, the tree-bark beige and cream flourishes, the pale, flecked breast and the short, stubby tail. As the owl turned its head it eyed me, then spread its dreamy wings and vanished into the trees. Moments like this can stay with us forever; my curiosity had been sparked again, and now I had found a new love. Owls! The Tawny Owl is another one of the animal species that is hard to know, and because of its nocturnal habits we have enfolded it in mythology, associating it with death and the uncanny, but in doing so had we ceased to pay the real creature proper attention? I wanted to find out, and went in search, and that’s how my new book was born.

I wrote about otters and owls, but it does not have to be the most charismatic species that draw us into sympathy with nature. It might be bats, bees, lizards or newts, just find your passion and many marvels can follow.

October 31, 2018

Blog > Interviews > Miriam Darlington