REVIEW

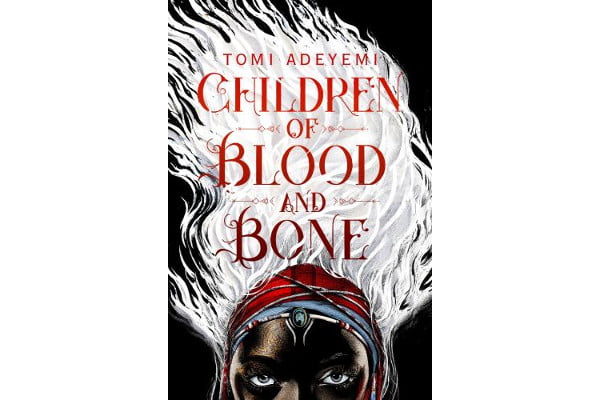

Children of Blood and Bone

Tomi Adeyemi

April 3, 2018

Blog > Reviews > Children of Blood and Bone

This review first appeared in the March 2018 issue of Books for Keeps, the UK’s leading, independent children’s book magazine. Follow them on twitter.

Feature Review by Geoff Fox

In a letter to her reader, Tomi Adeyemi hopes we “see a glimpse into my Nigerian heritage and the beautiful cultures and people Africa holds”. She wrote her novel “during a time where I kept turning on the news and seeing stories of unarmed black men and children being shot by the police”. Adeyemi is a Nigerian-American writer and creative writing coach based in San Diego, California. After an English degree at Harvard, she studied West African mythology and culture in Salvador, Brazil. Her “epic fantasy adventure,” we learn, is “soon to be a major motion picture from Fox 2000”.

Elements of this background are very evident in these 600 pages. There is violent graphic action, which will translate readily to the screen: a nautical battle between thirty vessels, staged in a flooded arena, howled on by a bloodthirsty mob, where it’s the last captain left alive who takes the prize; the excruciating torture of a girl we have come to care about; frequent hand-to-hand combat involving martial arts, lethal staves, majacite swords, fire and magic where brutal wounds are inflicted. There are so many deaths that they risk becoming as commonplace as those of a Hollywood blockbuster. Where a fatality does not result, recovery rates from catastrophic wounds – sometimes magic-assisted – are rapid and delays to the plot are minimal.

The ancient culture, especially its magic and mythology, is ever-present in an alternative Nigeria named Orisha. There are echoes of place-names we might recognise – Lagose or Eloirin, for example. Whole sentences appear in Yoruba, and individual words – gele, ahere, ashe (my keyboard cannot add the various accents) – are embedded in the prose, sometimes without contextual explanation. No glossary is provided. There are animals such as snow leoponaires, cheetanaires or gorillions. Now and then, those untranslated words and sentences such as, “Mother’s amber eyes scan the oleyes dressed in their finest, searching for the hyenaires hiding in the flock” may well distance or confuse – rather than intrigue – a young reader.

On the other hand, sometimes incongruously, the four young people (two brother/sister pairs, one of royal birth, the other from fisher-folk stock) speak in a contemporary idiom which may be intended to make YA readers feel at home: “you could’ve gotten us all killed”; “mess up”; “what part of that’s so hard to understand?”. Three of the four share the narration: a rebellious young princess; her older brother, schooled from birth to maintain his father’s tyrannical regime, destroying the magic at the core of Orisha’s culture and history; and young Zelie, the most developed character, struggling to balance her growing magical powers against the harsh responsibilities they bring with them. Along with Zelie’s brother, they play out the episodic quest adventure to a climax where everything is at stake in the struggle between the old magic (itself so easily misused) and the ferocious determination of the state to stamp out that magic and all its practitioners. As if this were not demanding enough, the plot is also driven by irresistible attractions which draw fisher-girl to prince and fisher-boy to princess, across racial gulfs and engrained values.

All three narrators tell their stories with painful self-awareness – especially the prince, torn between his father’s relentless training (‘Duty before self’), his disconcerting love for Zelie, and his realisation that he himself has the gifts of a ‘maji’. The action they describe is frequently frenetic, though it is sometimes there for its own excitement, rather than advancing the plot. The emotional intensity of the writing and the story’s wild originality make for exhausting reading but, for teenagers with stamina, rewarding returns. Though the ending sees ‘good’ in the ascendant, victory is far from conclusive or without cost. With a couple of pages to go, the spirit of Zelie’s ‘Mama’, briefly and poignantly reunited with her daughter, tells her, “It’s not over, little Zel. It’s only just begun”; and, I think, the last lines of the book open up the probability of a sequel.

Recommended age: 13-16yrs